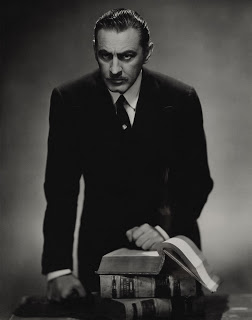

Photo courtesy of doctormacro.com

An MGM Production ~ Director: Richard Boleslawski , Art Direction: Cedric Gibbons and Alexander Toluboff, Costume Design: Adrian

Some years back I picked up a cocktail table book, The Romanov Family Album. Filled with photographs, many of them taken by Czar Nicholas himself, it captured his wife and children in every day moments, engaging in simple family pursuits. Hazy and seemingly touched by gossamer, these photos show signs of age and the newness of a budding technology, embraced by an enthusiastic photographer. It is amazing that these photos survive and give us this glimpse into the royal realm. It is this lost empire that is similarly glimpsed in Rasputin and the Empress.

It is fascinating to see this world depicted on the screen. There is a generosity towards the Romanov family that knowingly understands that extended family members and friends of the royal family were still living at the time of the making of this film (although MGM probably should’ve appreciated this more fully, but more on that later). Perhaps this accounts for this sympathetic portrait of an extremely privileged family, living an insulated, secluded life, aware only too late of the encroaching dangers. This depiction blurs the historical accuracy, to put it mildly. Here they are shown befuddled as to what could drive the Russian people to such anger and revolt, even as thousands gather in protest. While the attention to detail is evident in costume and design, it is far less a factor in the screenplay, which could definitely be truer to actual events.

There is much to love about Rasputin and the Empress. Most importantly for classic film fans, it is the only movie that features all three of the legendary Barrymore siblings, John, Ethel and Lionel. It is thrilling to see this trio together. Secondly, there is no doubt this is an MGM production. Perhaps due to the nearness of events, a wonderful attention to detail has been shown. The set design is beautiful, rich and layered. The gowns are sumptuous, beaded and laced. The uniforms* are impeccable and beautifully made. There is drama and romance, action and intrigue, star wattage and larger than life performances. Rasputin has the MGM touch and it shows.

Yet one wonders if Rasputin’s curse wasn’t upon the entire affair. There was a change of directors midway, a half-written script that was delivered to the actors in the mornings, and lawsuits post-production that ultimately amounted to pay offs of approximately $1 million dollars to extended family members, who objected to the creative license engaged in by the film makers.**

Reportedly Ethel was apprehensive and nervous regarding her involvement. Having appeared in silent films from 1914-1919 (and setting aside a 1926 home movie), she had spent the intervening years in the theater, returning for this, her first talking picture, following much persuasion and with the promise the film would be shot according to schedule. As is so frequently the case it was not, and following her contracted eight week shoot Ethel departed for the East Coast and theatrical commitments. But no matter. Much of the tension and action occurs between the brothers as they duke it out on screen with dueling dramatics and sibling stunts designed to scene steal and each over-act the other, first one, then the other and back again. They succeed beautifully.

Surprisingly, John did not end up in the role of Rasputin, luckily avoiding a resurrection of his performance in Svengali (1931). Rather he ends up as the romantic lead and rightfully so. It is certainly difficult to imagine Lionel, who despised playing romantic roles, as the aristocratic Prince Chegodieff, (a thinly disguised portrayal of an actual living Prince by the name of Yusupov), fiancé to Natasha, a Romanov niece depicted by lovely British theater actress Diana Wynyard in her film debut. Chegodieff not only shows depth of feeling towards his beloved but also towards the entire Imperial family. He is warm and protective, providing respectful, well-intended guidance. When that proves ineffective however, he turns to more drastic direct methods. Refreshingly, John plays this part with greater dignity and reflection than many of his other roles of this period. Still marvelously handsome, and remarkably so, we are afforded many glimpses of his famously perfect left profile, (probably far too many actually) and even at the age of fifty he is able to convincingly woo the young Natasha, throwing in just a hint of luscious naughtiness in a sweet early scene.

Ethel’s portrayal of the Czarina is filled with a great deal of emotion, her maternal love mingled with self-possession. Much of her performance is conveyed through her deep, dark eyes, whose warmth and sensitivity soften her regal poise. Her delivery is slow and measured, yet sometimes so much so she seems rooted to the floor. As she was known to base her portrayal upon her personal acquaintance with the Empress, it is difficult to know how much of this reserve is a royal visage or Ethel’s own trepidation regarding her return to film. Despite John’s reassurances that the cinematographer could work wonders, she was no doubt concerned that her five year absence would be evident upon a silver screen that so adored the luminous perfection of youth. Rasputin was her first encounter with the stylistic changes required for talking pictures, and the subsequent softening of her stage voice worked well to convey a loving, concerned and dignified presence.

Lionel in contrast seems to have had great fun with the evil machinations and malevolence of Rasputin. Playing with his beard (so ever present!) and engaged in wild-eyed manipulations, he becomes emboldened as his influence upon the Romanov’s, in particular the young heir apparent, the Czarevitch Alexei, (Tad Alexander), grows stronger. It’s riveting to watch Lionel throw himself into this role, relishing the opportunity to act his heart out and doing so in friendly competition with his brother and sister. I loved seeing Lionel’s lively, intelligent eyes behind all that make up and a beard, seeming to have a life of its own, floating in mid-air as he menacingly masticates his lines. His attempted seduction of royal daughter Maria is unbelievably creepy and the subsequent ravishing of Natasha even more so (though much has been left on the cutting room floor). Of course, this being a pre-Code film, he slaps Natasha as he cruelly diminishes her. Lionel could do kindly well, as he did in You Can’t Take It With You, but if you think of ‘Ol Mr. Potter (It’s a Wonderful Life), he could do evil even better. Add crazy and he could definitely steal a scene.

So steal away he does and while enjoyable, it does tend to give the movie a bit of an uneven pace. Between Ethel’s refined restraint, John’s debonair devotion and Lionel’s wild-eyed Rasputin, I sometimes felt as if I were watching this trio in several different movies. Each performs beautifully but the whole is somewhat less than its parts. This would appear to be not the fault of the Barrymores, who truly seem to devote their significant talents to this production, but rather to a sense of disconnect, not just between actors but between scenes. I was left with a vague suspicion that these talented thespians in large part directed themselves. Not quite true, but with the Barrymores you never know.

Given this unevenness, it’s hardly surprising to discover that shooting began with daily rewrites and an unfinished script. It was only at Ethel’s emphatic insistence that Charles MacArthur, later known for Gunga Din, Wuthering Heights and His Girl Friday, was finally brought in to pull together a messy screenplay already touched by at least twelve other screenwriters. The unevenness remains however and much of the plot moves through expository dialogues and sometimes monologues, delivered by Rasputin. His hold over the family is portrayed as mostly through the children, less through the Empress, furthering the historical inaccuracy. How I would’ve loved to have seen Lionel attempt to work his maniacal charms over Ethel!

(Spoiler Alert)

Yet despite these caveats, this is an entertaining film. There’s a fantastic scene between the Prince and Rasputin, who finally come to blows, the fighting going from table, to fireplace, to window, to wall, further wrestling and then out to the snow and ice. Whether this traversing about was planned or improvised it’s hard to tell but it’s a knock-down drag-out. John tries about six different ways to kill his brother in this scene, finally yelling in extreme exasperation “Why don’t you die?!?” and as Rasputin rises again, “Get back in hell!!” This is the stuff of high melodrama and tragicomedy and I enjoyed every minute of it; it’s the high point in a relatively somber film.

In one of the final scenes we hear an exchange between the Czar (Frank Morgan) and the Prince:

“Your majesty, I never believed that madman before. But one thing he said is roaring in my brain. He said when he died, Russia died. I’m afraid the cancer has been removed too late. We’re already destroyed”.

“No Paul. Russia is too great to be destroyed by any one man…… We have never injured our people … They will never injure us”.

These words frame the mindset of the royal family in perhaps the truest moment of the film. The Romanovs from all accounts, did not believe the love of the people would be entirely lost and yet, more untrue words were never spoken. It was not any one man, it was many.

Many of us know the end of this sad story and it’s certainly a cautionary tale, one of miscalculation by those who should know better, and yet are so insulated they are blind to the dangers encircling them. Secluded and cocooned in their wealth and privilege, they seem uncertain and unknowing, oblivious to the struggles of the people and confused as to how they might help. Every time we see these characters view their subjects, it’s from high above, too far removed, until the final moments.

This movie ends with a radiantly back-lit Russian Orthodox cross. The Romanovs were in fact, canonized and given saintly status by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1981. Recognized as martyrs who died for their strong and unceasing faith, it is yet this very faith that contributed to their compulsion to believe in the false teachings and guidance of Rasputin. There is no doubt that this movie attempts to portray the family favorably, in keeping with these Russian Orthodox views. While many in the western world might view this monarchy at best as antiquated and at worst as oppressive, there were others that viewed the annihilation of the last Imperial family of Russia with great alarm and despair. Certainly it was the end of royal reign as it had traditionally been known. The assassination of the House of Romanov realized the modernization of monarchy and the end of an era.

So perhaps, after all, it is this sense of distant rumblings that Ethel is trying to convey most of all in her tender portrayal of the Czarina. The Romanovs enjoyed life, neglectful of the needs of the countrymen over which they ruled. They danced, they played, they swam, they sang, they took photographs of it all and they were beautiful. We are presented here with not still photographs but moving images of a misguided family, filled with unfailing religious fervor and blind trust, insensible not only to the dangers without but to the dangers within, trusting those who might intend to manipulate and possess. Their faith in Rasputin, a false visionary with his own brand of mysticism, a fantastical belief in the Russian people and an aged, ancient system, ultimately led to their downfall. The insularity of privilege and elitism is a dangerous perch upon which to build one’s nest. Here, the people in the street prevailed, if only for a time.

Rasputin and the Empress gives us a small glimpse, despite its historical inaccuracies, into a lost time. For that and for the view it gives us of the extraordinary Barrymore triumvirate, it is well-worth a view.

Definitely Recommended

* If you’ve ever wondered about the inspiration for the uniforms in the Land of Oz look no further than the winter uniforms of Czarevitch Alexei and the Royal Guard as depicted here. Obviously MGM’s Wizard of Oz borrowed a little from this royal dynasty.

** Interestingly, the obligatory disclaimer disavowing “any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental” that we now see at the start of most releases is a result of these lawsuits with extended family.

Notes and Extras

Notes and Extras

In her autobiography Memories, Ethel Barrymore recalled an evening out during the filming of Rasputin:

I remember going to the “premiere” of a picture, the first one I had ever seen. This one in the middle of the depression was very different from those that I had heard and read about when the bystanders applauded the people who drive by them in big cars. This time there was no applause. The onlookers on the sidewalks were silent and sullen as people wearing furs and jewels rode by them in the big cars. It was a very uncomfortable experience.

Rasputin did not do well as the box-office. It lost more than one million dollars, and had cost more than two million to make. MGM general counsel J. Robert Rubin remarked “The damn thing stinks. Audiences won’t go near it”. Perhaps it was difficult for depression era audiences to feel sympathetic towards a wealthy privileged ruling family that was so obviously out of touch with the needs of the common people. Producing this film during the depths of the great depression may not have been the best timing. I can only imagine the audience confusion as to where their sympathies should lie.

The history and background drama surrounding the Romanovs, the making of the film and the Barrymore family are actually more interesting than the movie. If you would like to explore further:

- Pre-Code.com does a great job of providing some historical background and further thoughts about the movie and its comedic undertones. He takes a look at the imbalances in the film, while acknowledging the fun of seeing these three chew the scenery.

- Meanwhile Aurora at Once Upon a Screen beautifully describes Ethel’s relationship with her brothers, family dynamics and more about her impressions of the film. Her lovely words inspired me to promptly get my hands on a copy of Memories.

- If you are a Royalphile or just fascinated by those romantic Romanovs, The Romanov Family Album by Marilyn Pfeiffer Swezey is filled with vintage photographs of a lost time and place. Reminiscent of seeing vestiges of the Titanic or remains from Pompeii, it’s a book I have treasured for years for its glimpse into a world that is gone forever.

- Prince Yusupov actually had a hand in the killing of Rasputin. While he didn’t seem to mind that detail in the film he did apparently object to the inference that his wife had been raped by Rasputin (apparently she had never even met him), resulting in much editing and more hinting at shame than anything else. Ethel had intimidated that the extended royal family, now living primarily in France, might object to this plot development but once she returned to New York, MGM proceeded with the story-line that would ultimately lead to lawsuits and a very expensive out of court settlement.

- MGM’s fantastic in-house Art Director Cedric Gibbons was beautifully assisted by the Russian-born Alexander Toluboff, who had studied Russian architecture in St. Petersburg. Toluboff went on to three nominations for Art Direction, all in the latter 1930’s.

- This film marks not only Diana Wynard’s film debut but the first in her newly signed contract with MGM.

Notes and Extras

Notes and Extras

Notes and Extras

Notes and Extras