A First National Pictures Production ~ Director: Alfred E. Green, Based on a play by Joe Laurie Jr., Gene Fowler and Douglas Durkin, Screenplay by Kubec Glasmon, John Bright, Kenyon Nicholson and Walter DeLeon, Art Director: Jack Oakey, Costume Designer: Earl Luick

Money plays such a starring role in Union Depot that it deserves credit in the opening titles. Flowing smoothly from the first shot of the depot with a brief superimposed title sequence, the camera pans from the outside activity to the inside in a lovely long tracking shot that sweeps the vast space and then leads down to the small vignettes occurring inside. It’s a lovely panorama that pulls us into the heart of the story. Opening vignettes and glimpses into passersby and passengers tip a hand to the films knowing, cynical humor and snappy, swirling tempo.

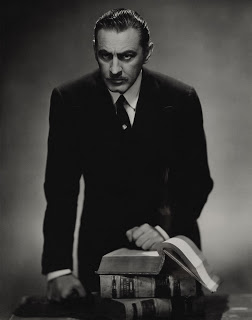

As the story unfolds, it is discovered that Chic, the dashing Douglas Fairbank Jr. and his fellow hobo, Scrap Iron, Warner’s fixture Guy Kibbee, have just been released from a 10-day stint in jail for vagrancy. By six that evening they find themselves at the depot. Fate, making its entry, intervenes. Across Chic’s path comes first a uniform, then a fortuitous conversation with an inebriated salesman, Frank McHugh in a short but memorable bit, so comically fixated upon his WWI reminiscences that he momentarily forgets his travel bag. Chic’s good fortune continues as Fairbanks is able to miraculously and perfectly fit into McHugh’s suit (!) and clean up a bit with a shaving kit. He also handily pockets some cash he finds conveniently tucked away. Chic has an opportunity to speak up about the cash as the bag is quickly retrieved but he just laughs; his first instinct is to fill his hungry belly. His second is to find a woman.

The young and luminous Ruth, a wide-eyed curvaceous Joan Blondell, appeals to him. They make quick conversation that leads them to a private room. Ruth conveys her hesitancy. She needs the money, $64 in fact, yet his assumption she’s a prostitute is an error, although she’s too desperate to let him know. We find that out just as he does: by the tears streaming down her face as he proceeds towards fulfilling what he believes is the plan and his own desires. Abruptly he slaps her once he realizes the truth of her situation, admonishing that she might not have been so lucky and could’ve found herself alone in a room with a man that wouldn’t have stopped. Ruth is a down-on-her-luck chorine, recovering from a broken ankle and in desperate need of money to rejoin her traveling company. Not only is she in need of cash, she is also keeping ahead of the advances of a lecherous deviant who has finagled her into reading stories of an increasingly salacious nature. Her fears are well founded as he is indeed revealed to be stalking her. Chic is at first interested in the sordid tale then concerned. But first things first. She’s hungry too and devours the meal he purchases for her. He downs the liquor himself.

Chic has moments of jarring harshness, particularly in the beginning of the film. He is conniving and thieving, scrappy and tough. Sometimes rough with women he can be good to them too. He has moments of decency and those come when he backs away from the things he might’ve done, such as he does with Ruth and later the things he does do. The strength of his character slowly emerges throughout the evening, unfolding just as the story does during a single night. As he gets used to the feel of money in his pocket and knows he’s got more stashed away, fate intervening again via a violin case stuffed with counterfeit bills, he grows a bit kinder and softens about the edges. Apparently having a full belly and a woman to look upon you as her “Santey Claus”, can put a bit of confidence into a man and allow for some magnanimity.

Despite being paired with this fellow traveler, we never see a similar change in Scrap Iron. Granted he’s a soft enough character to begin with, worn by time and trouble, and never having possessed Chic’s intelligence or charm. Yet it is of note that he is never seen to dine. In fact in the opening scene with these two, Chic reaches in a pocket, likely that of the found uniform, and pops a stick of gum into his mouth, leaving Ol’ Scrap Iron just standing there, pie-eyed and drooling over a described imaginary meal. Despite having access to the found cash, his appearance never changes. He remains a man on the outside looking in. Never satiated in any way, he wanders a capricious path. Kibbee plays this character as a bit of a sad clown, pulling tricks from his bag at improbable moments.

There’s a warm and satisfying romance at the center of this tale, helmed by two warm and charming romantic leads. Fairbanks can convey more with a grin and a tip of the head than just about anyone and Blondell shows her vulnerable side, one perhaps a bit closer to her own nature than her usual smart and sassy persona.

Surrounding this depression-era trio is a familiar cast of Warner Bros.-First National players, some uncredited. Aside from the already mentioned Kibbee and McHugh, Alan Hale, Dickie Moore, David Landau, Lillian Bond and even Lucille Laverne make an appearance. The movie is based upon a never produced play itself inspired by the successful Broadway hit Grand Hotel, already in the process of being turned into the classic 1932 film. Union Depot beat it to the punch by three months. The movie shows signs of being predicated upon the same premise, with the depot substituting for the hotel and a swirling cast of characters providing ambience. But the similarities to Grand Hotel end there. This is no glossy MGM production. The heart of this movie is in the streets, with Fairbanks playing forgotten man this time out.

Chic shows a nice agility on his feet both in taking advantage of opportunity, seizing a moment and dodging one, and there’s a nice action sequence that demonstrates his actual physical agility too. Jumping and veering from trains in the night, pursuing a truly bad man and turning into not only “Santey Claus” but a hero, Fairbanks Jr. echoes his father and his own gentlemanly heroics.

(Spoiler Alert)

Union Depot shows us that having the basics and a few luxuries can go a long way toward smoothing the rough edges and finding the diamond in the rough. The film was released overseas as Gentleman for a Day. With the cushioning comfort of a little dough, that is exactly who Chic is revealed to be. By movies end, we’ve seen him for who he truly is and so has Ruth, who tells him as much. This knowledge that each has seen the good in the other, and been made a better person for the experience, makes the ending that much more bittersweet, as money, either the pursuit of it or the lack of it, continues to define their paths in life. They share a warm kiss and embrace, exchanging the superficial kind of words that let us know they will likely never see each other again. Ruth leaves via train, Chic on foot, this time splitting a piece of gum with his road companion Scrap Iron, seemingly none the wiser, despite all that has transpired on this fateful evening.

Highly recommended, especially for lovers of the films of 1932.

This post is a part of the “Hot and Bothered” Blogathon July 9-10, 2016 hosted by CineMaven’s Essays from the Couch and Once upon a Screen

To read additional entries please visit: Once Upon a Screen or CineMaven’s Essays from the Couch

Notes and Extras

- Blonde Crazy with Jimmy Cagney was released in November 1931. It’s success led to this second co-starring role for Blondell, who gets second billing in the opening, just below the title. Aside from Fairbanks Jr., all other actors are credited at the end, creating a lovely immersive opening. This was Blondell’s thirteenth motion picture. By way of comparison, Fairbanks was already a veteran with this being his 42nd film!

- Next up for Blondell was another Cagney picture, The Crowd Roars. Concern was that Union Depot wouldn’t be finished on time, so much so there was talk of potentially re-casting her part in the Cagney feature. But that was easily remedied: Production was just started on the next film before this one was finished, leaving Joan scurrying back and forth between films.

- Joan’s reputation as one of the hardest working women in Hollywood was well-earned. In 1932 alone she appeared in nine films, with next in line being Kay Francis with eight, Una Merkel with seven and Loretta Young with six. Warner Bros.-First National Pictures knew how to work their hot properties, churning out quickly paced motion pictures in the process.

- The opening night for Union Depot was a big one with all stars on deck and held at Warner’s Hollywood Theater. Blondell, not usually one for an elaborate Hollywood social scene, attended dutifully, true to her consummate professionalism.

- The film was considered a personal hit for Douglas Fairbanks Jr. although New York Times reviewer Mordaunt Hall noted “it is questionable whether Mr. Fairbanks’s diction is quite suited to the lowly role. But he gives quite a satisfactory show.” Restrained and faint praise indeed. On the other hand, Variety , noting Chic brushes off some earlier, less substantial women, “for Ruth…he falls with the complete sangfroid of a sophisticated drifter”. Apparently Variety was more comfortable with the presentation of a gentleman hobo. They use some interesting language in this review overall so it’s worth checking out. I for one, love reading a good review.

- Disturbingly, Ruth is pursued by a perverted deviant who is obviously stalking her with extremely ill intent, however Blondell and the actor (George Rosener) actually share no scenes together. This is perhaps a good thing. Horribly, Joan was the victim of a brutal rape before her career in entertainment began. Detailed in her biography, Joan Blondell: A Life Between Takes by Matthew Kennedy, she remained silent about it for over four decades until finally revealing it in her thinly-disguised semi-autobiographical novel, Center Door Fancy. This is one of those instances when I truly wonder how the actress felt during filming, particularly when describing her fear and desperate need to get away.

- Fairbanks, along with Robert Montgomery, was one of the first men in Hollywood to enlist and serve in 1941, before the United States officially entered WWII. Truly a renaissance man he lived to the age of 90.

- For a nice peek at a much younger Fairbanks, try Loose Ankles, a 1930 early talkie with Loretta Young. A slightly naughty teen-age rom-com, it features a twenty-one year old Fairbanks romancing a just barely seventeen year old Loretta Young. Both are beyond cute and adorable as they get into one silly situation after another. Incredibly he was already married to Joan Crawford at the time, having hitched his fate to hers in 1929. They untied that knot after just four years but what a four that must have been!

Notes and Extras

Notes and Extras